The Scam - Part One

The one thing we've thought about endlessly over the last five years is how we came to be scammed by Contractor A in the first place. Looking back, it seems really obvious, like when somebody shows you how a magic trick is done. But at the time it was artfully managed to keep us from having the time or space to see what he was doing.

There are a few basic elements to running a scam. First is to keep everything moving, so nobody is able to concentrate on any one thing. Then you have to make sure the marks -- the people you're scamming -- don't talk to each other or have enough time to start asking questions. And finally, when you've gotten as much money as you can get, leave town. And Contractor A did pretty much all of that with us. We're not proud to admit that we got scammed, but we do hope our experience will help everybody else out, especially people who are considering hiring him for a job.

(Is it possible that he did all this without intending to scam us? Maybe. But the preponderance of evidence says this was deliberate, especially the later concealment of documents and attempts to confuse us over the bookkeeping.)

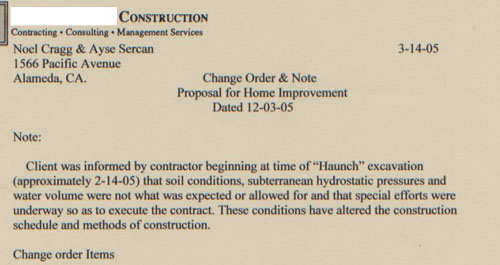

The first part of the scam was a flurry of change orders, some legitimate, many of them, according to a construction expert witness we hired, completely fraudulent. But if you keep the change orders coming, the mark gets in the habit of signing off on things, even things that he shouldn't sign off on. Like this one:

That was just a little note at the top of an unrelated change order. That he insisted Noel had to sign. He would not leave without getting Noel's signature. So Noel made a note at the bottom saying "rec'd" with his signature and the date, because he was not going to sign off on a change order that was also acknowledging a lie.

The other aspect of it was an aggressive offense. Contractor A kept billing us, and Noel, being an honest person, kept paying the bills. But the bills themselves seem to have been based on completely dishonest numbers. We don't know what he did with all that money, but it sure didn't go under our house, and I've never seen a construction company run so badly that it chewed through three times as much in overhead as it did in job costs. At one point we calculated the amount of money that went under our house in actual labour costs and materials, and it was under $30,000.

(We invite Contractor A to come here and refute this. We'll even let him stay anonymous. He sure tried to tell us many times how we were wrong about the bookeeping, but his logic always came out, in transcription, looking like a shell game huckster's patter.)

We did ask him to explain to us why, when we had paid him $80,000, he was claiming he was still $40,000 in the red -- even when he'd showed us a profit and loss statement that showed him to be well in the black. Being in the red at that point would have meant he'd spent $120,000 on just the excavation, which would have been $40,000 a week. That amount of money on an excavation where the excavation subcontractor has given you a fixed bid of $20,000 for the whole job is insane.

Here's the transcript of our conversation with him on the subject:

Ayse: I just keep going back over and I can't figure out why we should pay you anything more than we've contracted to pay you. I go through your profit and loss statement and it shows me that you've got about $60k in cash from this project alone.Contractor A: I don't know, but, OK.

A: I mean, you paid yourself about $31k and you had a bottom line of -- I added it up to $26,667.94, you added it up to $23,849. Whatever. Only $10k of that is [still] owed to Contractor B, so that's -- you've still got a profit there.

Contractor A: Uh-huh.

A: And...

Contractor A: You've forgotten the, um, general liability insurance which is $4,867 -- something like that -- and there is another 500-600 in unemployment insurance. My, my, my figuring, which I spread out and you can see, leaves me with $7,457 above wages. $7,457 above wages. [note: when Contractor A starts stammering like that, he is lying; it's quite the tell]

A: In profit, in addition to your own wages.

Contractor A: Above my wages. Don't say "profit"... because there's... no

A: That's what it is. It's a profit and loss statement. If it's in the black, it's profit, if it's in the red, it's loss.

Contractor A: That's overhead... and profit.

He honestly thought that by throwing numbers all over the place, he could convince us that it was entirely reasonable for a small firm with two employees and one part-time bookkeeper to rack up tens of thousands of dollars in overhead in six weeks.

The other thing he did was try to divide and conquer. At one point in the process Noel got tired of dealing with his aggressive offense. We hadn't yet caught on to the scam, but keep in mind that Noel has a full-time job that is not just being a patsy to a con artist. He asked me to deal with Contractor A because he needed to be able to concentrate on work a little. In my next phone conversation with Contractor A, Contractor A said, "Noel said you didn't know much about construction and he didn't want me to talk to you."

"Oh, really," I said, trying to imagine a world where Noel would think I didn't know about construction. And also trying to figure out why Contractor A would think Noel, who had specifically asked me to deal with Contractor A for a while, would have said he didn't want me to.

"Yep. You know how men are about women and construction."

I do know how men are about women and construction, however, I also know how my husband is about women and construction, and these are not the same thing. When somebody relies on a cultural stereotype to try to lie to me about Noel, I always catch them.

Of course, the only person who has ever done that to me is Contractor A.

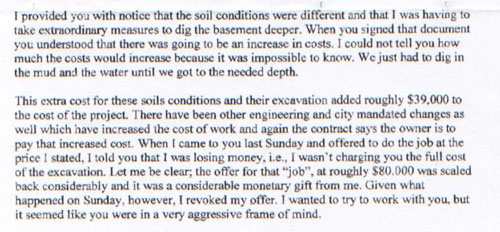

This is the letter he sent us after refusing to honour his contract. He had begun to insist that he had provided us with notice of the conditions.

His estimates for the cost of excavation included a lot of weird dollar figures and random numbers -- he'd start talking about $39,000 excess cost for excavation, then confuse it with talking about the cost to complete the job, then throw in a few other things to try to make it harder to follow the train of the conversation.

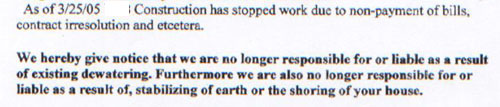

By the time we got this letter, we knew we'd been had. He was trying to assert his version of events as truth over and over, as if yelling it would make it true. The only thing left was for him to leave town like a good scam artist, and he did that:

In case you were wondering, you cannot simply notify somebody that you no longer have liability and have that be legally binding. And the assertion about non-payment of bills was, unfortunately, not true. We should have stopped paying him much sooner than we did.

Technorati Tags: construction, foundation, foundation replacement, legal action, renovation horrors

posted by ayse on 04/14/10